I’m currently studying a Masters in Environmental Management and one of our assignments was to write a opinion style blog post on a topic around Resource Management or Circular Economy. I’d noticed the increase in discarded e-vapes and, being a follower of LessWasteLaura since COP26, had seen that it was something she was trying to raise awareness of. I submitted the assignment in November last year and thought I’d publish here too as, thankfully the topic has gained some recent momentum, with it being discussed in Scottish Government on whether there should be a ban.

Written in October/November 2022 and submitted to Glasgow Caledonian University as part of a module assignment:

DISPOSABLE VAPES- A TICKING TIME BOMB OR ALL SMOKE WITHOUT FIRE?

Scotland has made some great progress recently towards reducing waste and promoting circular economies. With the most recent ban in June 2022 on single use plastics (including plastic cutlery, straws and catering containers) the country has seen a positive change in behaviours.

In 2023, the proposed introduction of a return deposit scheme will encourage the return and recycling of consumer goods such as drinks bottles and containers.

Why then do we seem to be ignoring the fact that, daily, people are throwing electronic waste into their household waste or worse still, on to our streets? What item am I referring to? Disposable electronic vapes.

What are vapes?

Vapes, or e-cigarettes, were introduced to the UK market in 2005 as an alternative to smoking and, initially to reduce or stop smoking habits.

The vaping market has grown substantially since 2005 with a wealth of product lines now available including disposable vapes in addition to reusable units with refillable cartridges. These disposable offerings are incentivised at point of sale and, as a result, demand has shifted to favour the disposable product lines.

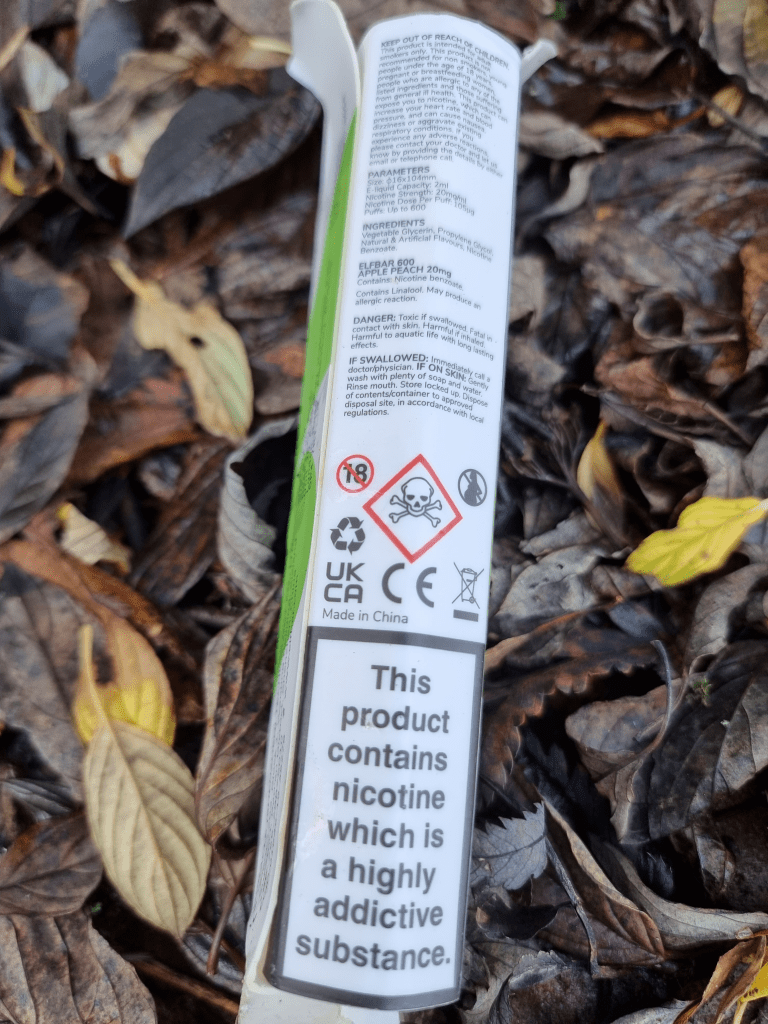

Disposable vapes last between 1 – 2 days for the average user. Not only does this type of short-term use fundamentally contradict the circular economy aim of extending the useful life of products, but they contain finite materials and some which are toxic.

Research by Material Focus in 2022 estimates that approximately 3 million vapes are binned in the UK every week, of which approximately 1.3 million are disposables.

Truth Initiative’s research suggests that 51% of young vape users throw disposable vapes in normal waste bins, 17% into household recycling (not intended for e-waste) and 10% throw them onto the ground.

Almost half of vape users didn’t know how to recycle the products, which is unsurprising as suppliers are failing to provide adequate information to consumers.

Wrap (a Climate Action NGO) has conducted research suggesting 84% of UK households unintentionally contaminate recycling, with approximately 155,000 tonnes of e-waste being binned in the UK annually. Many EEE (Electrical and Electronic Equipment) products contain PVC (a synthetic plastic polymer) and BFRs (Brominated Flame Retardants). These are carcinogenic and released throughout the products life.

What’s inside a vape?

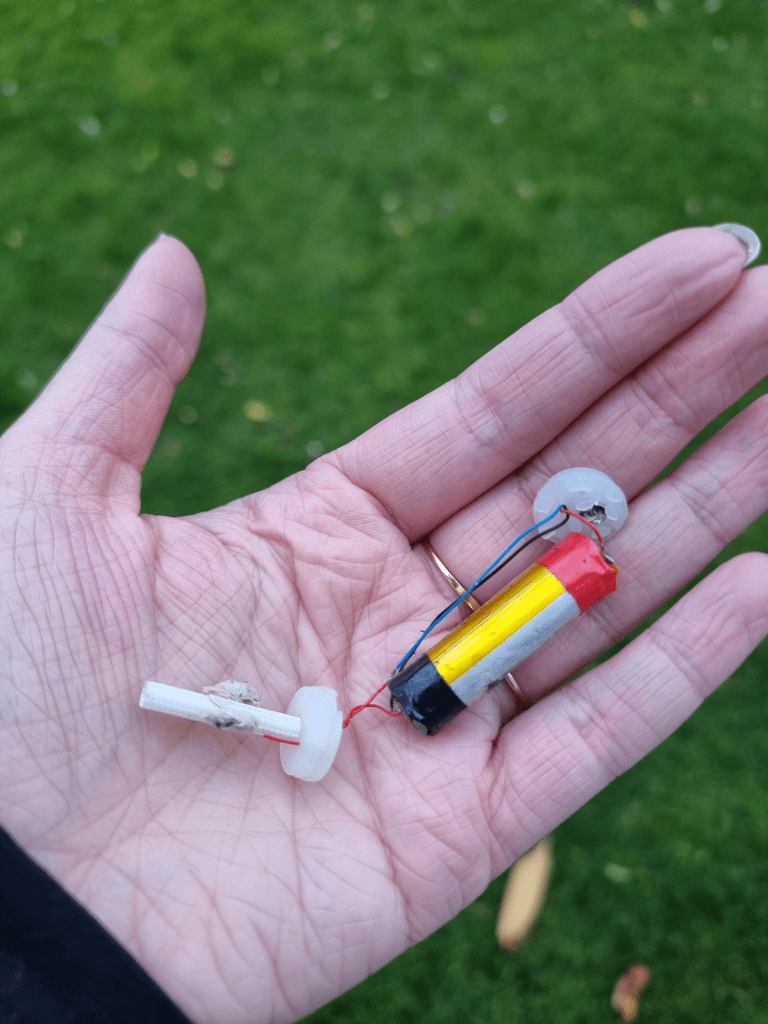

Vapes consist of an outer plastic shell, containing: A lithium battery, wires connecting to a heating element and a nicotine cartridge, filled with plastic fibres soaked in propylene glycol and flavourings.

Why should we be concerned?

If properly segregated, many of the materials can be recycled. However, with the majority of vape units being disposed of incorrectly, the materials are not handled responsibly, causing potential harm to humans, the environment and other life forms.

Many discarded vapes are by roadsides where they are likely to be struck by traffic. As well as the environmental impacts these products have, they can pose an immediate hazard, especially in a damaged state, to young children and animals.

I recently found a discarded vape in a local play park, which had exposed battery and wiring. My 3-year-old child attempted to pick it up.

Recyclability and future considerations

Every three years the EU reviews critical materials and, in 2020, Lithium was added to the list due to increased demand. The EU report estimates that up to 18 times more lithium is required by 2030 compared to our current demand, and almost 60 times more by 2050. Currently 78% of EU’s demand of lithium is supplied from Chile and, despite EU being able to mine Lithium at home, it needs to leave the EU to be processed. Being a key component in electric vehicle batteries and energy storage, sustainable sources of Lithium are fundamental to our roadmap to net zero.

Currently there are estimates that around 0% of Lithium demand is satisfied through recycled material.

The increase of demand of electric vehicles will require increased amounts of lithium and expanding the mining and smelting infrastructures to support this is risky, lengthy and highly capital intensive. Reusing batteries can therefore reduce the reliance and the environmental impact of additional mining. The annual disposal of vapes equates to approximately 10 tonnes of lithium, which could contribute towards 1200 batteries for electric vehicles.

Estimates predict there will be no major supply risk to lithium up to 2050 however these estimates assume that 25% of demand will be from recycled lithium and, as previously mentioned, at present almost no lithium is being recycled.

Additional Impacts

As well as the challenge of meeting our growing lithium demand, the incorrect disposal of vapes leads to challenges within our waste management industries.

If vapes are disposed of through general waste they will likely end up in landfill or at a waste treatment site, where the primary fire risks are due to batteries. There is a real risk that, if the products end up in a waste treatment centre, they could ignite and cause harm to employees and the overall operation.

A BBC news article on zombie batteries suggests there were 250 fires in waste treatment sites between 2019 and 2020 associated with lithium-ion batteries, an increase of 25% on the previous year.

In July 2021, a fire broke out in outer Glasgow at a waste treatment centre, contracted to deal with NHS clinical waste. The fire was large enough to severely damage the site and had a knock-on effect in waste processes and operations across NHS Scotland.

What’s the solution?

Finding information regarding the correct disposal means for vapes is difficult and that’s because, currently, there is no perfect solution. Vapes should be treated as electronic waste but this isn’t something that is easily accessible to people so solutions need to be introduced at point of sale.

Material Focus are pushing for more accessible recycling with collection points available in stores. On a similar note, ESA launched a campaign called ’Take Charge’ to encourage the proper disposal and handling of batteries.

Depending on the available infrastructure to support lithium recycling, products could be returned through an incentivised deposit return scheme. However, this is a challenge since lithium is not commonly recycled at present.

Some people are calling for outright bans of the product. However, for many, the use of vapes is an alternative to smoking cigarettes. However, with a growing focus on global sustainability and a shift towards circular economies it seems to me ridiculous that companies can sell such products when other single use/disposable items have been banned. A return to the refillable/rechargeable vapes seems a logical initial response.

Awareness and education need to be addressed, tackling both manufacturers and consumers. Climate PHD researcher and Scottish social influencer Laura Young (lesswastelaura) has recently been raising awareness of the issue and, at the time of writing, an article was published by the BBC.

Accelerators of change

Pressure needs to be applied on manufacturers to design better products and return to refillable, reusable solutions that are designed for better reuse or recyclability.

Legislation also needs to push manufacturers and wholesalers to understand their part; changes to alcohol laws were made in Scotland to ban price offers that could incentivise bulk sales. This could be replicated to discourage bulk buying rather than incentivising multi-buy discounts on single-day use items.

Finally, the government needs to address the challenges around having the right infrastructures to support effective recycling and reuse. Despite the European legislative framework for WEEE, a significant proportion of consumer electronic items are not recycled properly and are exported to other countries.

Despite the recent coverage in the news, I continue to ask myself:

Why do we wait for something to become a big problem before we address it?

How many animals will attempt to consume discarded vapes and how many children will pick up broken electronics at their local play park?

How many times will we read about waste treatment sites tackling fires?

What will it take for us to address this growing problem?

References

Angerer, 2009. Lithium fur Zukunftstechnologien – Nachfrage und Angebot unter besonderer Beruucksichtigung der Elektromobilitat. Germany: Fraunhofer ISI.

BBC News, 2020. The explosive problem of ‘zombie’ batteries. [Online]

Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-54634802

[Accessed 11 November 2021].

BBC News, 2022. Should disposable vapes be banned?. [Online]

Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-63037553

[Accessed 24 November 2022].

ESA, 2022. Take Charge. [Online]

Available at: https://www.takecharge.org.uk/

[Accessed 5th November 2022].

European Commission, 2020. Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability. [Online]

Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/42849/attachments/2/translations/en/renditions/native

[Accessed 05 November 2022].

European Raw Materials Alliance, 2022. [Online]

Available at: https://erma.eu/

[Accessed 5th November 2022].

Hageluken, 2015. Closing the Loop for Rare Metals Used in Consumer Products: Opportunities and Challenges. In: W. S.Hartard, ed. Competition and Conflicts on resource Use. Switzerland: Springer International, pp. 103 – 120.

Hayder, 2022. Preprocessing of spent lithium-ion batteries for recycling: Need, methods, and trends. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 168.

Helmers, E., 2015. Possible Resource Restrictions for the Future Large-Scale Productions of ELectric Cars. In: W. S.Hartard, ed. Competition and Conflicts on Resource Use. Switzerland: Springer International, pp. 121 – 131.

LessWasteLaura, 2022. Ban Disposable Vapes. [Online]

Available at: https://www.lesswastelaura.com/ban-disposable-vapes.html

[Accessed 03 November 2022].

Material Focus, 2022. One million single use vapes thrown away every week contributing to the growing e-waste challenge in the UK. [Online]

Available at: https://www.materialfocus.org.uk/press-releases/one-million-single-use-vapes-thrown-away-every-week-contributing-to-the-growing-e-waste-challenge-in-the-uk/

Mishra, 2022. A review on recycling of lithium-ion batteries to recover critical metals. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, Volume 10.

Prior, 2013. Sustainable governance of scarce metals: The case of lithium. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 641- 462, pp. 785 – 791.

Scottish Government, 2021. Scotlands Deposit Return Scheme. [Online]

Available at: https://www.gov.scot/news/scotlands-deposit-return-scheme/

[Accessed 05 Nov 2022].

Truth Iniative, 2021. A toxic, plastic problem: E-cigarette waste and the environment, s.l.: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/harmful-effects-tobacco/toxic-plastic-problem-e-cigarette-waste-and-environment.

Weetman, C., 2017, 2021. A Circular Economy Handbook. 2nd Edition ed. s.l.:Kogan Page.

WRAP, 2022. [Online]

Available at: https://wrap.org.uk/taking-action/climate-change

[Accessed 2022].